Africa is missing out on a key pillar of the global digital economy

Despite leading the world in grassroots adoption, Africa is largely absent from the infrastructure layer of the crypto ecosystem. The continent is effectively invisible in the latest rankings of global crypto mining, and the economic gap is becoming impossible to ignore.

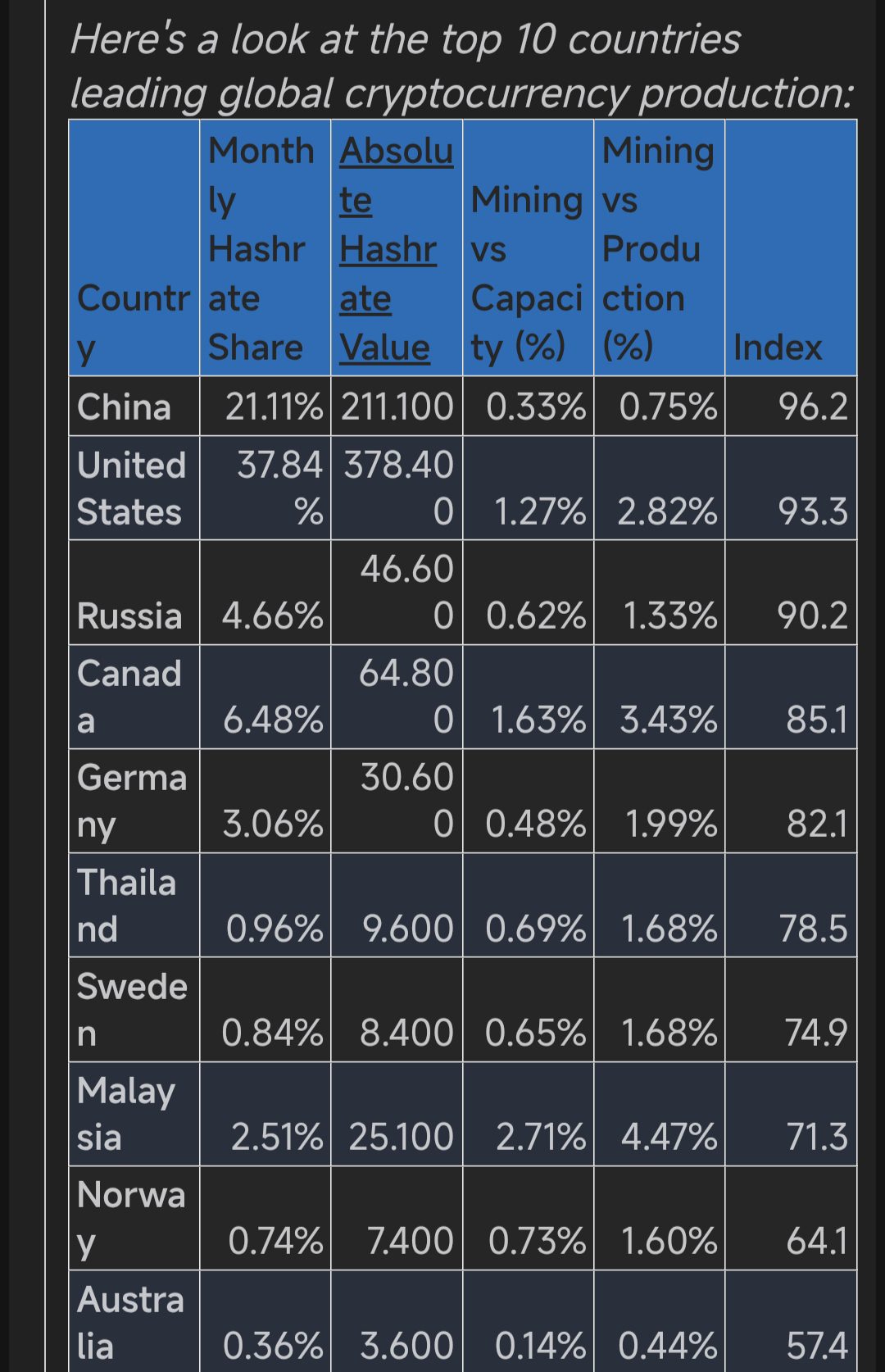

A November 2025 study by decentralised exchange ApeX Protocol reveals the extent to which crypto mining has concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere, highlighting a stark disconnect: while African nations are rapidly adopting digital assets, they remain completely shut out of the industry’s value creation.

That absence carries real economic consequences.

According to the research, China alone produces more than one-fifth of the world’s crypto output. Remarkably, it uses just 0.33% of its total power capacity for mining. The United States goes further, handling nearly 38% of global crypto mining, with heavier pressure on its electricity grid.

Russia, Canada and Germany complete the top five. Each has built a balance between computing power, grid resilience and energy efficiency. Even countries with smaller economies, such as Malaysia and Thailand, are making deliberate moves.

Malaysia now dedicates close to 5% of its electricity production to cryptocurrency mining, among the highest ratios globally.

What stands out most is not who is on the list, but who is not. No African country appears among the top global crypto producers. This absence is striking given Africa’s growing role in cryptocurrency adoption, peer-to-peer trading, and blockchain innovation.

Across Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa and Ghana, crypto usage has surged over the past five years. Africans increasingly rely on digital assets for remittances, inflation hedging and cross-border payments. Yet when it comes to the infrastructure layer of crypto, where value creation is capital-intensive and long-term, Africa remains largely excluded.

There are structural reasons for this.

Many African power grids remain fragile, expensive, or unreliable. Large-scale crypto mining requires stable electricity, predictable regulation and access to capital.

Countries like China and the US benefit from mature energy markets, surplus power capacity, and clear industrial policy frameworks. In comparison, African governments often view mining as a risk rather than an opportunity.

That caution, however, may be costing the continent a seat at the table.

Meanwhile, it’s important to point out that the absence is not due to a lack of potential. Many African countries hold structural advantages that mining operators actively seek, like surplus energy capacity, especially from hydroelectric, solar, and wind sources.

Others flare or waste natural gas that could be converted into mining power.

The ApeX Protocol index assessed countries across four areas. These included global hashrate share, total computing power, electricity efficiency and the strain placed on national grids. Scores ranged from 0 to 100, rewarding countries that mine at scale while keeping power systems stable.

China topped the index with a score of 96.2. The US followed closely on 93.3. Russia’s relatively low energy usage kept it competitive, while Canada’s higher draw from its grid slightly lowered its score despite strong output.

Energy efficiency is rewriting the crypto mining map

The data makes one thing clear. This is no longer about cheap electricity alone. It is about efficiency, grid planning and regulatory clarity.

Germany is a useful example. Despite high energy prices and a complex power market, it controls over 3% of global crypto production. Mining there consumes less than 0.5% of national electricity capacity. That balance keeps political pressure low and investor interest steady.

Malaysia shows the opposite risk. Its aggressive allocation of energy to crypto mining boosts output but increases grid strain. As the ApeX Protocol spokesperson noted, cryptocurrency mining has become an economic sector governments cannot ignore. Checks and balances are now essential.

Africa could learn from both models. Instead, many governments continue to treat crypto mining as a regulatory threat rather than an industrial opportunity. In some cases, outright bans remain on the table. In others, electricity tariffs are unpredictable, discouraging long-term investment.

This caution has costs. Crypto mining is capital-intensive. It creates demand for data centres, grid upgrades, fibre connectivity and skilled labour. It can anchor renewable energy projects that struggle to attract industrial buyers. It also keeps digital value creation within national borders rather than exporting it.

Without a coordinated framework, Africa risks repeating a familiar pattern. Raw resources and energy potential will exist, but the value creation will happen elsewhere.

The global crypto mining industry is consolidating fast. Hashrate is concentrated in countries that make early, deliberate choices. Every year of delay narrows the window for late entrants.

For African economies facing youth unemployment, fragile currencies and energy monetisation challenges, this is a missed strategic play. Crypto mining is not a cure-all. But neither is it a fringe activity anymore.

Leave a Reply