Despite Leading 35% of Nigeria’s Informal Businesses, Women Earn the Least

Before dawn breaks over Lagos’s Mile 12 market, a female tomato vendor is already preparing for the day ahead. Like countless women managing informal enterprises throughout Nigeria’s bustling open markets, her income hinges not only on sales volume but also on the consistency of her expenses and her ability to access essential financial services.

This individual experience mirrors broader national trends revealing that while women constitute a significant portion of informal traders, they often find themselves at the bottom of the financial hierarchy within this sector.

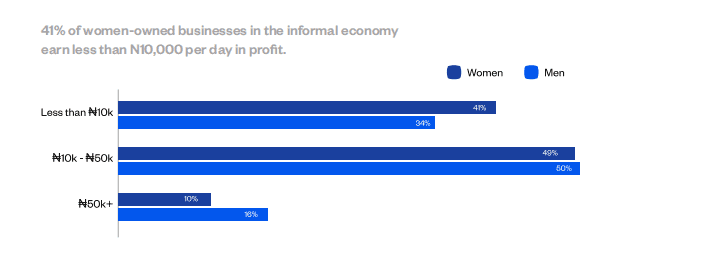

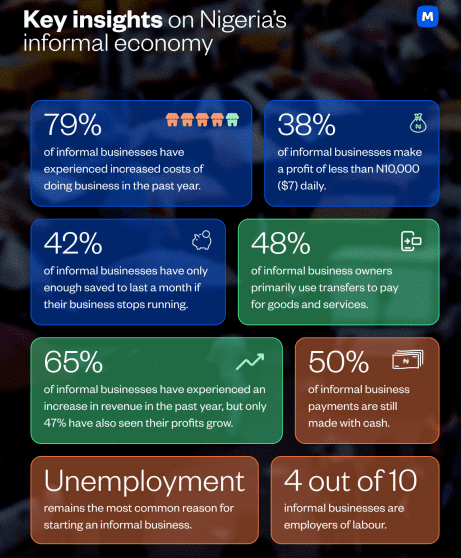

Data from the 2025 Informal Economy Report by Moniepoint indicates that women own approximately 35% of informal businesses in Nigeria. However, 41% of these women-led ventures generate less than ₦10,000 in daily profit, compared to 34% of businesses owned by men.

Conversely, only 10% of women’s informal businesses earn over ₦50,000 per day, whereas 16% of male-owned businesses surpass this threshold. This disparity highlights the tight profit margins women operate within, leaving minimal scope for reinvestment or scaling their enterprises.

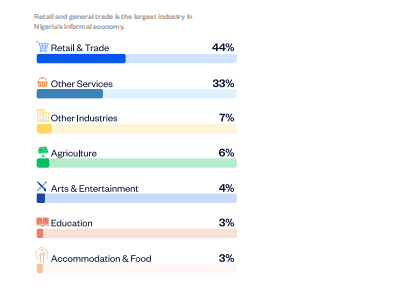

These statistics shed light on the underlying dynamics of Nigeria’s informal economy. Women predominantly engage in visible retail activities-selling groceries, fresh produce, household items, and everyday necessities in local markets nationwide. Yet, ownership does not equate to financial empowerment.

Many female traders survive on razor-thin profits and face barriers to financial tools that could enhance their business potential. Their daily income is often consumed by fluctuating costs, unpredictable market prices, and unavoidable levies. Despite their prominent presence, their economic influence remains constrained.

Limited Access to Substantial Loans for Women in Informal Trade

Gender inequality is stark when it comes to financing. Merely 6% of women in the informal sector have secured loans exceeding ₦1 million, while men are twice as likely to obtain such substantial credit.

This financial gap restricts women’s capacity to grow their businesses. For instance, a woman vending household goods in markets like Oshodi or Aba typically depends on daily savings to replenish stock. When credit is available, it often comes from informal sources such as friends, rotating savings groups, or local moneylenders, many of whom impose steep interest rates or require social collateral. Access to formal banking remains largely elusive.

The report highlights that cooperative savings groups are a lifeline for many women traders. Approximately 74% of informal business owners save regularly, with a majority of women participating in informal savings mechanisms like ajo and esusu.

While these savings groups provide some financial relief, they lack the flexibility and capital scale necessary for substantial business development. For example, a woman who sets aside ₦500 or ₦1,000 daily over a month can cover restocking or household expenses, but this amount rarely supports expansion or investment in improved equipment.

Another significant challenge is the daily levy many market traders must pay. Nearly half of informal businesses are subject to such fees. A trader paying ₦500 daily in market dues ends up spending roughly ₦125,000 annually-often exceeding the value of their initial stock investment.

This means a large portion of their revenue is absorbed by unavoidable operational expenses.

Unlike formal taxation systems that often come with documentation and potential benefits, these daily levies are typically collected informally by market associations or local authorities.

Women bear a disproportionate share of this burden due to their concentration in retail and food sectors, which operate on slim margins and require daily cash flow. Inflation exacerbates these pressures; when prices for staples like tomatoes or cassava rise, female traders face reduced sales and profits but must still pay consistent levies.

The 2025 Informal Economy Report further reveals that women traders are less likely to have formal business registrations, less likely to secure loans from formal financial institutions, and less likely to own the market stalls they occupy.

This absence of formal assets restricts their ability to use their businesses as collateral, confining many to subsistence-level operations. It also excludes them from financial aid programs that require official documentation or security.

Despite the informal economy’s vast scale and influence-especially in retail and food sectors dominated by women-these traders remain marginalized.

Trust issues also play a role. Many women are wary of formal banking due to previous encounters with hidden fees, bureaucratic delays, or stringent requirements. Consequently, they prefer to rely on financial arrangements they can control.

However, this cautious approach limits their opportunities to build credit histories, access insurance products, or benefit from government-backed financial initiatives.

In summary, women are indispensable to Nigeria’s informal economy, driving daily commerce and supporting local communities. Yet, they face systemic exclusion from financial structures that could empower them to grow. They shoulder the highest costs with minimal security, underscoring the urgent need for inclusive financial solutions tailored to their unique challenges.

Leave a Reply