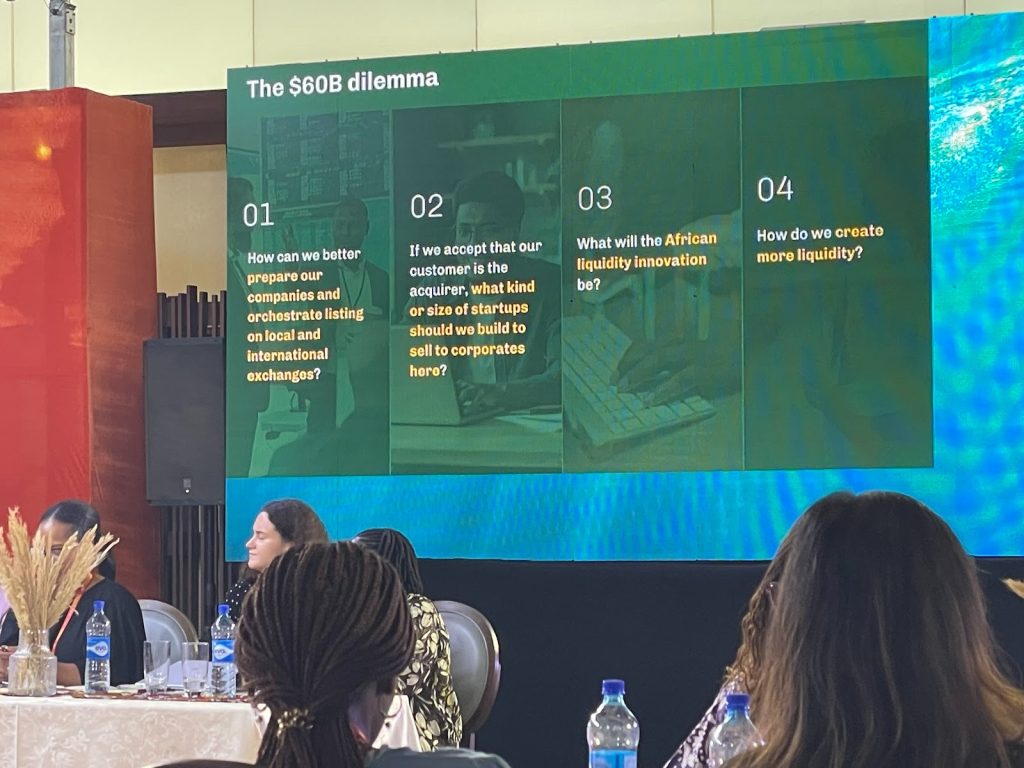

African startups have $60B to return. How will they do it?

At the African Prosperity Summit 2025, held from November 12 to 14, 2025, founders, fund managers, policymakers, and investors gathered to discuss the state of capital in the continent’s technology system

The main event, held on November 13, 2025, featured a plethora of conversations with key players in the African business ecosystem and African private capital leaders.

Setting the tone of the event, Kola Aina, founding partner of Ventures Platform, highlighted that there is a significant gap between capital raised and exits achieved in the tech ecosystem.

In his opening speech, Aina shared that since 2020, African startups have raised a total of $18 billion, and fund managers with dedicated African strategies have raised an additional $2.3 billion. Using a Venture Capital (VC) return on investment projection, Aina estimated that in total, “If you piece that together, we’re talking about something in the region of $20 billion [range] dedicated to African VC strategies.”

In VC economics, a 3x return (DPI—Distributed to Paid-In capital) is generally considered the benchmark for a successful fund. With a 2x to 3x return, Aina shared that the DPI expectation by 2035 is $40 to $60 billion for the VC market to be regarded as a sustainable market that makes an impact and delivers returns on investment.

The deadline for these returns is “by about 2035” based on the standard 10-year lifecycle of a venture capital fund. If capital is raised between 2020 to 2025, the fund must liquidate (exit) its assets between 2030 to 2035.

Aina urged VCs to engage in the conversation: “There is a direct correlation between liquidity and participation.” It is clear, and he emphasised, there is a $60 billion to contend for, and this dilemma is what the summit set out to answer, especially as this number is growing with capital pouring every day from the venture ecosystem.

The strategic pivot: Unicorns vs. SMEs

The first step to returning this capital would seem to be an operational reality check. During the Liquidity as Leverage panel, industry leaders argued that the “growth at all costs” model often creates companies that are too expensive to be bought.

Bunmi Akinyemiju, CEO of Venture Garden Group, argued that founders must be clear on whether they are building a venture company or an SME (small to medium-sized enterprise).

Akinyemiju said, “If you’re building an SME, you price the SME…and you sell it to somebody that buys an SME,” or simply generate dividends. The disconnect arises when founders build SMEs but price them like Unicorns, making exits impossible.

On the same panel, discussing catalysing exits to sustain the cycle, Ross Strike, SVP, Investor Relations at Moniepoint, added that exit readiness isn’t just about sales; it’s about building a “business machine” with strong governance and financial controls from day one.

However, Daniel Adeoye of Verod Capital warned founders of a “strategic debt,” noting that the market can sometimes penalise companies for becoming too big, limiting the pool of potential acquirers to international giants. He said, “Usually ticket sizes in this market [in this continent] are $50 to $100 million. So there’s such a thing as being a strategic fit.” By this, Adeoye implied, there is a sweet spot where local banks, telcos, and conglomerates can comfortably acquire a company in Africa.

The ‘strategic debt’ growth trap he warns of can happen when a startup becomes too expensive for local acquirers, yet too risky or complex for global ones. As companies are defining their operational landscape, they should be wary of this. By raising at a high valuation today, founders are “borrowing” the expectation of a massive exit tomorrow, and if companies cannot repay the debt by securing one of the few global buyers available, they default on their liquidity promise to investors. It is often better to sell earlier to a local strategic buyer for a modest, guaranteed return than to hold out for a massive global unicorn exit that might never happen.

The capital shift: Patience and alternatives

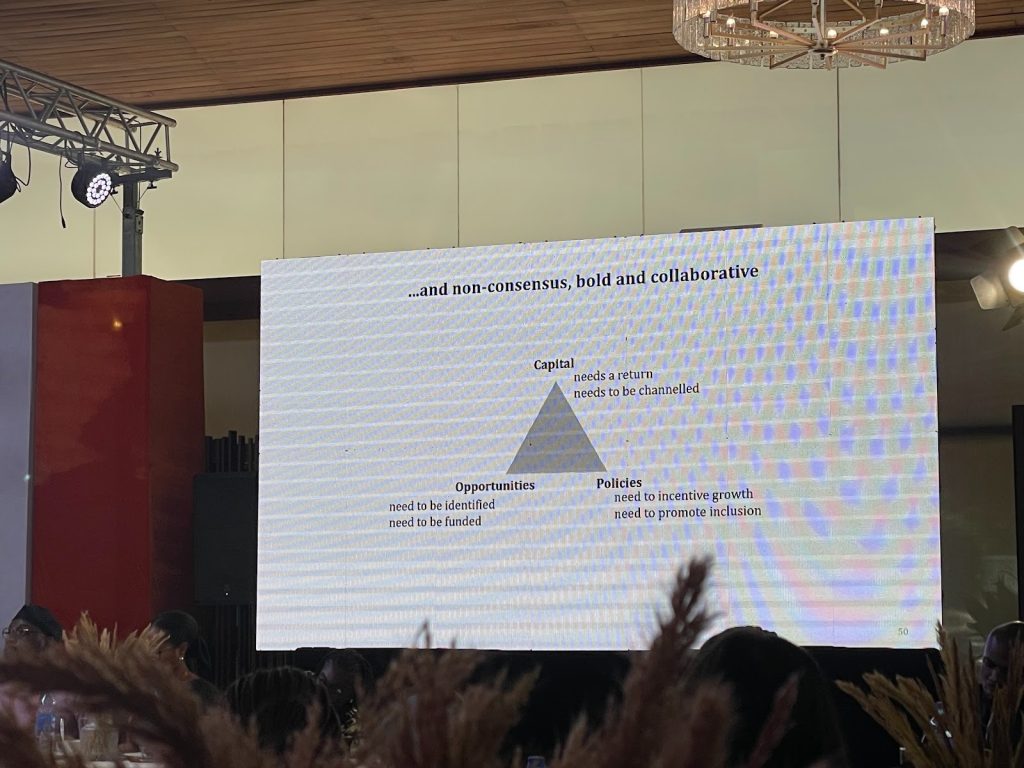

If the operational model must change, so must the capital timeline. Chirantan Patnaik, Director at Ventures Platform, noted in his presentation, ‘A View from the Capital Stack’, that for a $5 billion fund to succeed, the ecosystem requires a $160 billion exit value. He questioned whether the standard 10-year fund lifecycle is realistic for the African context.

This sentiment was echoed by Bolaji Balogun, CEO of Chapel Hill Denham, during the panel session on ‘Policy and markets: building for the long term.’ Balogun argued that the traditional private equity model of a three-to-five-year exit horizon has “failed in Africa”. The traditional Private Equity (PE) model is time-bound. A PE firm raises a fund with a mandate to return the money in roughly 10 years. This forces them to invest, grow the company, and exit (sell) within a three-to-five-year window

“Create long-duration funds,” Balogun advised. ”There’s a world-class model that works [and can be] found in the UK market. 103 of the 350 companies in the FTSE 350 are listed investment trusts. And what listed Investment Trusts allow you to do is basically to bring liquidity to an inadequate asset class.”

Unlike a standard VC fund that must liquidate after 10 years, a Listed Investment Trust is a company listed on a stock exchange (like the London Stock Exchange or NGX). This way, the fund is permanent. The fund can hold the company for 10, 15, or 20 years without being forced to sell. If an investor wants their money back, they don’t force the fund to sell the startup. Instead, they simply sell their shares in the Trust to another investor on the stock market.

Hayo Afman, Regional Director Africa for Alder Tree Investments, offered a solution from the family office perspective. Speaking on the panel on ‘Betting on Africa: The Global Investor Perspective,’ he noted that family offices, which manage generational wealth, do not have the same aggressive liquidity timelines as VCs.

“We don’t need to see liquidity for the next [couple of] years,” Afman stated, emphasising that patient capital allows assets to mature properly.

Also, equity is not the only route, and this concept was elaborated in the panel session about structuring alternative capital pathways.

Lexi Novitske, General Partner at Norrsken22, noted that debt financing is an effective alternative for asset-heavy models, predicting a rise in “consumer-backed financing” where customers essentially fund the product they use.

“What’s going to come longer-term in some African markets is more consumer-backed financing, [by] consumers [who] want to have an [earned] product,” Novitske said. “ I think Piggyvest already does this for several of its customers. But it could be anything from owning a share of property to having a portfolio of maybe super credits.”

The market unlock: Domestic liquidity

Returning $60 billion requires a marketplace that can absorb it. Patnaik used India as a case study, noting that its ecosystem matured because domestic institutional investors eventually outpaced foreign ones. This means seeking participation from non-traditional investors, such as financial institutions and corporate venture capital (CVCs), and building for the continent’s near-term evolution rather than its current state.

With India, he showed:

- Domestic capital is key: India’s ecosystem matured not just because of foreign VC, but because domestic institutional investors eventually outpaced foreign ones.

- Retail participation: He highlighted the role of “Systematic Investment Plans” (SIPs), where ordinary citizens invest small amounts (e.g., $3/month), creating a massive pool of domestic capital.

To put Patnaik’s thoughts simply, startups earn in local currency (Naira, Cedi, Shilling) but raise in Dollars, and domestic capital can speed up returns by aligning the currency of investment with the currency of revenue.

Ultimately, the path to returning $60 billion involves a shift from relying solely on foreign acquisitions to engineering local exits, embracing patient capital, and building businesses priced correctly for the market they serve.

Leave a Reply