AWS, Microsoft, may never build data centres in Nigeria

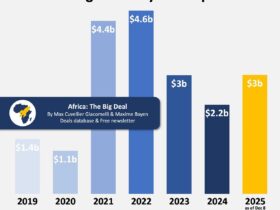

The data centre capacity in Nigeria has been projected by several reports to grow significantly over the next few years.

Estate Intel estimates that it will rise from 56.1 megawatts (MW) in 2025 to more than 218 MW by 2030. Verraki, an African business solutions company, projects growth to 400 MW in its Opportunities in the Rising Data Centre Economy in Africa report, while data from Mordor Intelligence forecasts a rise to 279.4 MW.

Although the projections vary, there is a clear surge of interest in the data centre market, especially given the developments seen so far in 2025.

This year, MTN announced West Africa’s largest Tier III data centre, with an initial 4 MW capacity, and planned expansion to 14 MW. A few months later, Airtel revealed plans to build one eight times larger, with an IT load of 38 MW.

Equinix, which already operates two data centres in Nigeria — LG1 and LG2 —plans to build a third, LG3, by Q1 2026. The company, which has 270 data centres globally, says $22 million will be invested in the first phase of LG3.

Despite these promising developments in Nigeria’s data centre market, the country remains a challenging environment in which to build such facilities.

In a conversation with Techpoint Africa, Ranjit Gajare, Chief Growth Officer at Sterling and Wilson Data Centre (SWDC), explains why Nigeria is a strong candidate for data centre investment and the obstacles that may still deter investors.

Data centre investment is growing, but hyperscalers are not interested yet

SWDC has built data centres for hyperscalers such as Microsoft and AWS across the Middle East, India, and Africa. According to Gajare, digitisation remains one of Africa’s biggest drivers of data centre demand.

From enterprises moving workloads to the cloud to governments digitising health, education, and citizen services, the volume of data generated has surged.

He notes that colocation companies — businesses that rent out data centres — are the ones investing the most in Nigeria and Africa’s wider data centre market. Equinix, one of the world’s largest data centre companies, already operates two facilities in Nigeria and plans to build a third.

Similarly, Digital Realty acquired Nigeria’s Medallion Data Centre in 2021 for $29 million.

“The largest colocation companies are in Africa, and I think they make up the largest share of the demand,” he says.

However, the picture is different for hyperscalers such as Microsoft, AWS, and Oracle. Gajare explained that although these companies want to deploy data centres where demand is strongest — and Nigeria, with its population, tech ecosystem, and multiple cable landings, is a prime candidate — expansion decisions depend on far more than market potential.

A key factor is how easy and predictable it is to set up a data centre in a given country. “If I were a hyperscaler, the biggest challenge would be the regulatory approvals,” Gajare says.

Compared to places like Dubai, where clearances can be issued in 48 hours, it can take months in African countries like Nigeria.

The approvals required to set up a data centre include building permits, environmental permits, electricity connections, and water sanctions.

These take longer in Nigeria and other African countries, largely due to bureaucratic hurdles. “It involves negotiating and interfacing with government departments where there could be inefficiencies, delays, and even unexpected costs,” he explains.

Setting up a data centre in Africa is too costly

For a multimillion-dollar facility where delays translate directly into losses, unpredictability is a deal-breaker.

Unfortunately, bureaucracy is not the only factor deterring data centre investment in African countries.

Supply chain constraints also make it a risky endeavour. “If material is stuck at the port or there is a stoppage in construction, your capital gets locked without generating value,” Gajare explains. Every additional week on a stalled site is money burned.

Talent is another concern. “You might not find efficient and reliable contractors in the market,” he says.

Data centre construction is highly specialised, and a mistake in electrical, cooling, or structural design can compromise the entire facility. Reliable contractors with true Tier III or Tier IV experience remain scarce on the continent, making quality assurance a serious challenge.

There’s still hope

Despite these challenges, Gajare believes hyperscalers will eventually enter the Nigerian market more directly. He sees AI workloads as a major driver; AI systems require extremely high power density, which encourages hyperscalers to build their own purpose-built facilities rather than rely solely on colocation providers.

Nigeria’s data centre market is growing fast and attracting world-class operators. However, the next phase of growth, especially the phase that brings hyperscalers, will require the country to simplify its approval process.

Leave a Reply