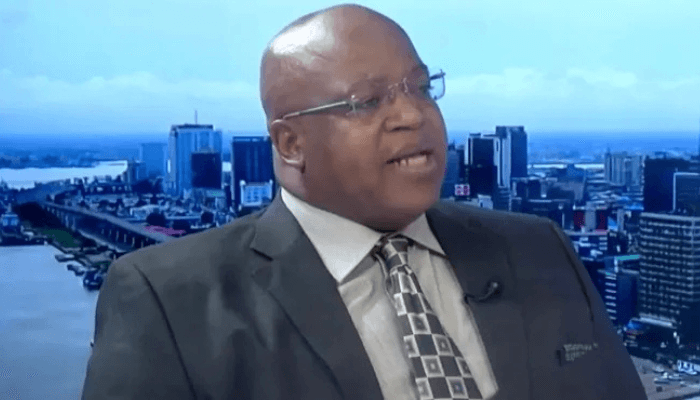

How Nigeria can slash airfares, stop capital flight – Nwuba

Alexander Nwuba is currently the President of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, the 2nd Vice President of the Aviation Safety Roundtable, and Special Adviser to the President of the Federation of Tourism Associations of Nigeria. He is a core adviser and takes a leadership role in Aerius Ireland’s airline rollup strategy to build a regional African airline in pursuit of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM). In this interview with IFEOMA OKEKE-KORIEOCHA, he shares a detailed roadmap for democratizing air travel in Nigeria by slashing exorbitant fares, urging the government to move past mere rhetoric and enact urgent policy reforms.

Do you think flying in Nigeria still remains a privilege for the few despite current insecurity issues on our roads?

Flying in Nigeria remains a privilege for the few. Out of more than 210 million citizens, only 0.02 percent — about 42,000 people — regularly fly. That leaves 99.98 percent of Nigerians; over 209 million people are excluded from aviation. This is not just a statistic; it is a stark reminder that air travel, which should be a driver of national integration and economic growth, is still inaccessible to almost everyone.

The fares tell the story. A one‑way economy ticket from Lagos to Abuja costs between ₦105,000 and ₦152,000. Internationally, Lagos to London averages $750–$1,100 (₦950,000–₦1.4 million). These prices are not simply about the dollar exchange rate. They are the sum of fuel surcharges, airport service fees, regulatory levies, bank interest on double‑digit loans, and import duties on aircraft and spare parts. Instead of reducing these burdens, new charges such as the API levy are being introduced, further inflating fares. Every cost in aviation eventually lands on the passenger’s ticket.

How do you think this narrative can be changed in Nigeria?

At my last meeting with the Director‑General of the Nigeria Civil Aviation Authority (NCAA) and the wider sector, I stressed the need to release the grip on complementary sectors like general aviation. Current certification and surveillance models are built on the template of large scheduled airlines, stifling innovation. Regulations prevent non‑scheduled carriers with the Air Transport Licence (ATL) and Air Operator’s Permit/Certificate (ATOP) licenses from wet leasing small aircraft — the very aircraft that could serve Nigeria’s growing network of state airports. Without freeing general aviation and enabling smaller carriers to operate flexibly, Nigeria cannot expand access to flying across its regions.

What other reforms would you suggest?

Another urgent reform is bringing maintenance and training home. Nigerian airlines spend up to $1 billion annually on overseas maintenance. A single heavy “C‑check” can cost $4–6 million per aircraft, excluding ferrying and logistics. Every dollar spent abroad is capital flight. If even half of these work were done locally, Nigeria could save hundreds of millions annually, stabilize airline finances, and reduce fares. Employment would also surge. Nigeria’s aviation workforce today numbers about 159,000–200,000 jobs. Developing local MRO facilities and training centers could double employment to 400,000 by 2030, while keeping skilled talent in Nigeria and creating new export revenue streams.

Does the government have a role to play in making these reforms a reality?

None of this will happen if the government continues to pretend that the marketplace alone will solve aviation’s problems. Talk is cheap; actions must be deliberate. Nigeria cannot become a hub by magic or slogans. It requires policy direction from the Federal Government. The strongest airlines in the world are backed by public investment, yet Nigeria has a robust private airline sector that deserves support. A national carrier with long‑haul aspirations, combined with regional and domestic private operators, creates the model for a successful and effective African aviation system.

Yesterday’s model of mega‑hubs like Emirates is outdated in a world where truly long‑haul aircraft now exist. Today is not about hubs but gateways. Nigeria has the opportunity to become Africa’s gateway — where Nigerian carriers can carry their own generated traffic and foreign airlines can feed traffic through Nigeria into Africa. This is a new paradigm, a realisable opportunity, and one Nigeria can seize immediately if the government drives the policy mix of public and private collaboration.

What economic benefits do you see these reforms creating?

The economic benefits are clear. Nigeria’s freight and logistics market is valued at about $10.95 billion in 2025, projected to reach $15.05 billion by 2030. Aviation can anchor this growth by building the infrastructure that distributes goods through gateway airports, leading to warehouses, jobs, and e‑commerce platforms that center Nigeria as a beneficiary of AfCFTA. Transport GDP already contributes hundreds of billions of naira per quarter; with aviation integrated into trade facilitation, this figure can rise sharply.

The time to act is now. The NCAA must modernise its framework to encourage general aviation, small aircraft operations, and flexible leasing models. The Federal Government must stop piling on new levies and instead drive deliberate policies that combine public investment with private sector strength. Nigeria can be Africa’s gateway, but only if leaders choose action over rhetoric. By 2030, 126 million new passengers could be flying, fueling growth in tourism, trade, and investment, and turning aviation into a true engine of national development.

Leave a Reply