State budgets, big ambitions: Are Nigeria’s governors finally getting serious about development?

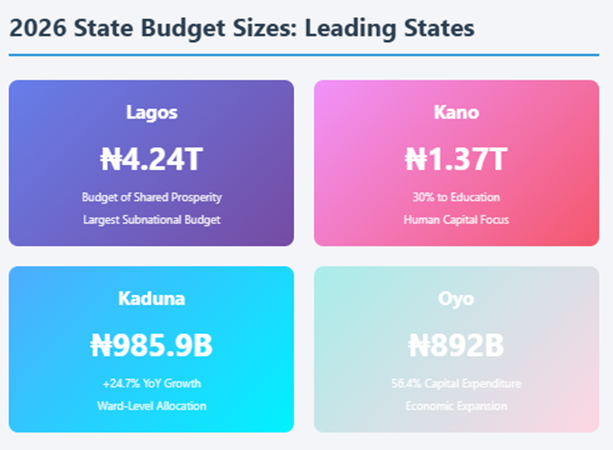

The season of budget speeches has begun, and Nigeria’s governors are outdoing one another in a contest of trillion-naira ambition. Lagos, Kano, Kaduna, Oyo and several others have now laid their 2026 spending plans before their Houses of Assembly. On paper, these blueprints promise roads, classrooms, clinics and “shared prosperity”. The harder question is whether they add up to a credible pathway to growth, welfare and inclusion—or merely another round of optimistic arithmetic. What is striking this year is not just the size of the numbers but the pattern. Across leading states, we see bigger envelopes, often 20-30% above last year, a visible tilt towards capital spending and human capital investment in education, health and infrastructure, yet persistently fragile financing marked by heavy dependence on FAAC, rising wage bills and debt service, alongside historically weak budget implementation.

Read also: Governors lift 2025 education budgets to ₦3.6trn

Lagos: The mega-budget as development strategy

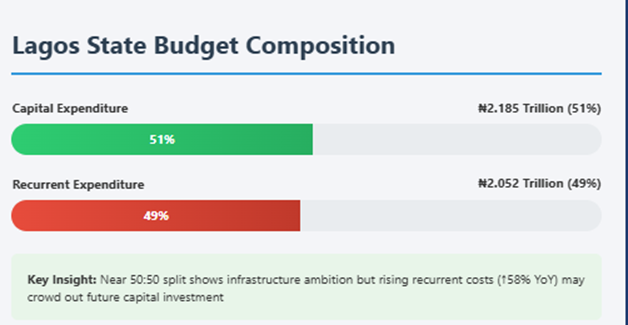

Lagos has, predictably, gone big. Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu has presented a ₦4.237 trillion “Budget of Shared Prosperity” for 2026—by far the largest subnational budget in the country. Capital expenditure is put at ₦2.185 trillion, while recurrent spending rises to ₦2.052 trillion, meaning just over 51% for capital and 49% for recurrent. Relative to 2025, the capital envelope grows only modestly at about 5.5%, but recurrent spending jumps by more than 58%, driven by personnel costs, overheads and debt service. Revenue is projected at ₦3.994 trillion, anchored on a strong increase in internally generated revenue and higher expected federal transfers, with the deficit scheduled to shrink by roughly 39%.

Sectorally, Lagos says it will prioritise economic affairs encompassing infrastructure, transport and job creation, alongside education and health. The development logic is straightforward: in a state that already contributes around a third of national IGR, sustaining growth demands continuous expansion of transport networks, housing, schools and hospitals, or congestion will choke off productivity and erode welfare. The risk, however, lies in execution and realism. Past budgets have struggled to achieve full capital implementation. And while Lagos’ IGR base is by far the strongest in the federation, it is not immune to macro headwinds, high interest rates and slower real growth. A near-50:50 split between capital and recurrent spending is defensible for a complex megacity, but the politics of a ballooning wage and overhead bill could begin to crowd out investment over time if not carefully managed.

Read also: Breaking: Lagos budgets N4.2trn for 2026

“First, recurrent spending is not the enemy; poorly structured recurrent spending is. Teachers, doctors, engineers and extension workers are all “recurrent”.”

Kano, Kaduna, Oyo: Human Capital gets more room

Further north and west, three states—Kano, Kaduna and Oyo—offer an interesting counterpoint. Their budgets are smaller in absolute terms, but their composition is arguably more developmental.

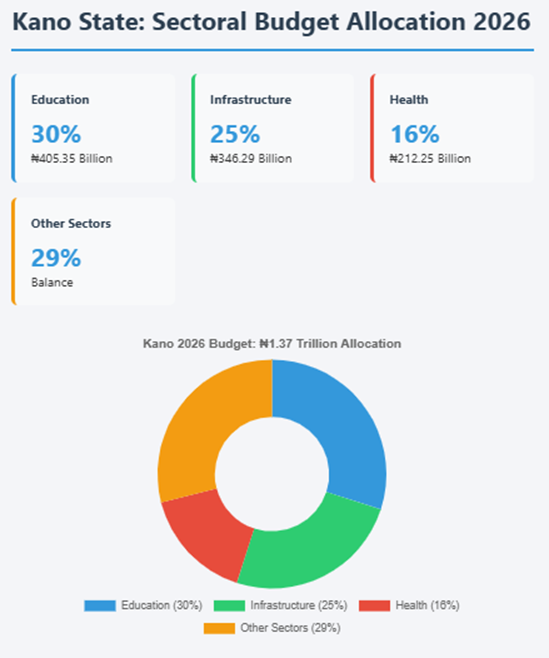

Kano’s governor, Abba Kabir Yusuf, has sent a ₦1.36–₦1.37 trillion 2026 budget to the House. Education takes the single largest share at about ₦405.35 billion, or 30%; infrastructure follows with ₦346.29 billion, or 25%; and health receives ₦212.25 billion, or 16%. Compared with the 2025 “Budget of Hope”, which already devoted 31% to education and 16% to health, the new plan reinforces a clear human-capital bias. Kaduna has proposed a ₦985.9 billion 2026 budget—about 24.7% higher than in 2025—with an explicitly capital-heavy orientation. Infrastructure takes around 20% of the envelope, while education, health and agriculture each receive 15%. In a novel twist, the state plans to allocate ₦100 million to each of its 255 political wards, totalling ₦25.5 billion, for small community-driven projects—a modest but symbolically important nod to inclusion and local ownership.

Oyo’s “Budget of Economic Expansion” for 2026 comes in at ₦891.99 billion, up from about ₦684 billion in 2025. Capital expenditure is put at roughly ₦502.85 billion, or 56.4%, with recurrent at ₦389.14 billion, or 43.6%. The governor has flagged infrastructure, education, healthcare and agribusiness as the key engines of expansion. Taken together, these three budgets illustrate a broader trend that independent analysts have been picking up. A recent Dawn Commission analysis of South-West state budgets shows capital spending now outpacing recurrent spending, with the ratio of recurrent to capital falling from 0.87 in 2021 to 0.74 in 2025—a sign that more resources are being pushed towards long-term infrastructure and assets. Kano’s 2025 budget already allocated 57% to capital; the 2026 proposals in multiple states are continuing that shift. On paper at least, state governments appear to be “saying the right things”: more roads and schools, less salary-only budgeting. But budgets are not development. Execution is where the story turns messy.

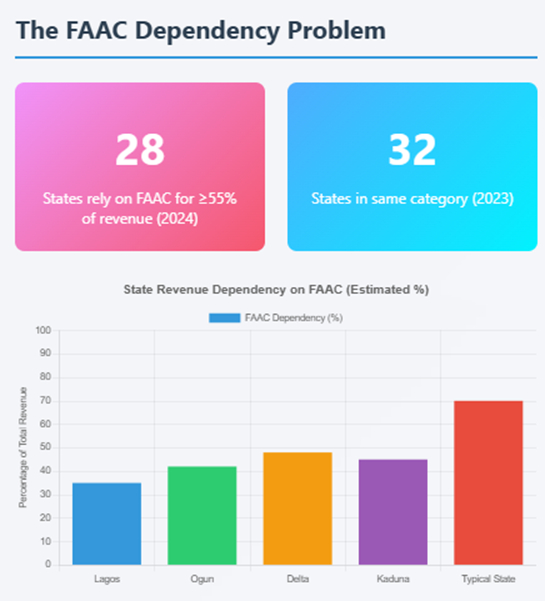

The FAAC problem: Ambitious plans on fragile foundations

The basic constraint facing most states is unchanged: they do not control their revenue base. BudgIT’s latest State of States report notes that in 2024, 28 states relied on FAAC transfers for at least 55% of their total revenue, only a small improvement from 32 states the year before. Lagos, Ogun, Delta and Kaduna have built relatively stronger IGR capabilities, but the typical state still lives and dies by the monthly allocation from Abuja. At the same time, states have been spending more than they earn, with personnel costs growing by about 23%, overheads by 63% and capital expenditure by nearly 120% year-on-year in the latest cycle—a sign of aggressive expansion, but also of fragility if revenues disappoint.

Read also: Turn budgets into weapons of security accountability

Health and education, the sectors most frequently name-checked in budget speeches, often suffer from poor execution. In one of its state case studies, BudgIT shows how a government that allocated over 75% of total spending to capital in 2024 still managed to implement only about 35% of its education budget and roughly 63% of health. The pattern is familiar: spectacular announcements at the beginning of the year and quiet virement and under-execution by year-end. Against this backdrop, the 2026 state budgets look like a high-wire act. Governors are betting that elevated oil prices, improved tax administration and ongoing federal reforms will keep FAAC flows buoyant enough to underwrite their plans. That may hold in the near term. But the underlying vulnerability—heavy dependence on a volatile, federally controlled revenue source—has not gone away.

Development, growth, welfare: What these budgets could mean

If the 2026 budget promises were fully delivered, their impact on development could be meaningful. Larger capital envelopes and double-digit shares for education, health, agriculture and infrastructure are precisely what Nigeria’s subnational governments need to unlock growth and social mobility. Better roads, power and logistics can cut business costs, expand market access and support SMEs. In states like Lagos and Kano, infrastructure spending can turn chaotic urbanisation into structured agglomeration, boosting productivity. Sustained 15-30% allocations to education and health, if actually spent, would gradually repair dilapidated schools, reduce out-of-school rates and improve primary healthcare—especially if targeted to rural and peri-urban communities. Kaduna’s ward-level allocations and Oyo’s rhetoric of “economic expansion” hint at a desire to push resources closer to citizens, not just fund grand capital projects in state capitals. Properly managed, such schemes can reduce feelings of political and spatial exclusion.

But there are also risks and blind spots. First, recurrent spending is not the enemy; poorly structured recurrent spending is. Teachers, doctors, engineers and extension workers are all “recurrent”. The danger is that wage bills reflect political patronage rather than genuine service delivery needs, leaving classrooms understaffed while political appointees proliferate. Second, many budgets still under-invest in social protection and women- and youth-focused programmes relative to the scale of poverty and vulnerability exposed by recent inflation shocks. The rhetorical focus on infrastructure can crowd out low-cost but high-impact interventions like cash transfers, school feeding, maternal health schemes and targeted support for smallholder farmers. Third, high interest rates at the federal level—with the CBN’s policy rate still at 27% and state borrowing largely priced off sovereign yields—raise the cost of financing deficits. States that those who roll over short-term bank loans and issue domestic bonds to plug budget gaps will pay dearly, potentially diverting future revenues from classrooms to creditors.

What should citizens and firms watch?

Budgets are moments of clarity—they reveal priorities. But they are also, often, works of fiction. For businesses, households and civil society, three metrics will matter more than the speeches. Capital implementation rates will tell the real story of how much of the promised roads, schools and hospitals actually get built, and where. Citizens should track mid-year and end-year performance reports, not just appropriation bills. Revenue realism matters critically—are IGR and FAAC projections plausible or built on rosy assumptions? States that repeatedly over-projecting revenue and under-delivering capital spending are running a political Ponzi scheme. Pro-poor and pro-inclusion spending deserves scrutiny beyond headline percentages for education and health. How much is going to primary and secondary education versus universities, to primary health versus prestige tertiary facilities, and to rural wards versus capital cities? Initiatives like Kaduna’s ward allocation deserve close examination: will they be transparent and community-driven, or captured by local patrons? In an environment where inflation is finally easing but real incomes remain under pressure, the quality of state spending will be as important as the quantity. A trillion-naira budget that pays salaries late and leaves boreholes unfinished is less developmental than a leaner budget that reliably delivers textbooks, immunisations and all-weather roads. The early 2026 budgets suggest that many governors have absorbed the language of development economics: human capital, infrastructure, and inclusion. The challenge now is to prove that this is more than a change in script—that Nigeria’s states can turn ambitious spreadsheets into tangible improvements in growth, welfare and opportunity.

Dr. Oluyemi Adeosun, Chief Economist, BusinessDay

Leave a Reply