What NGX data says about who employs Nigerians the most

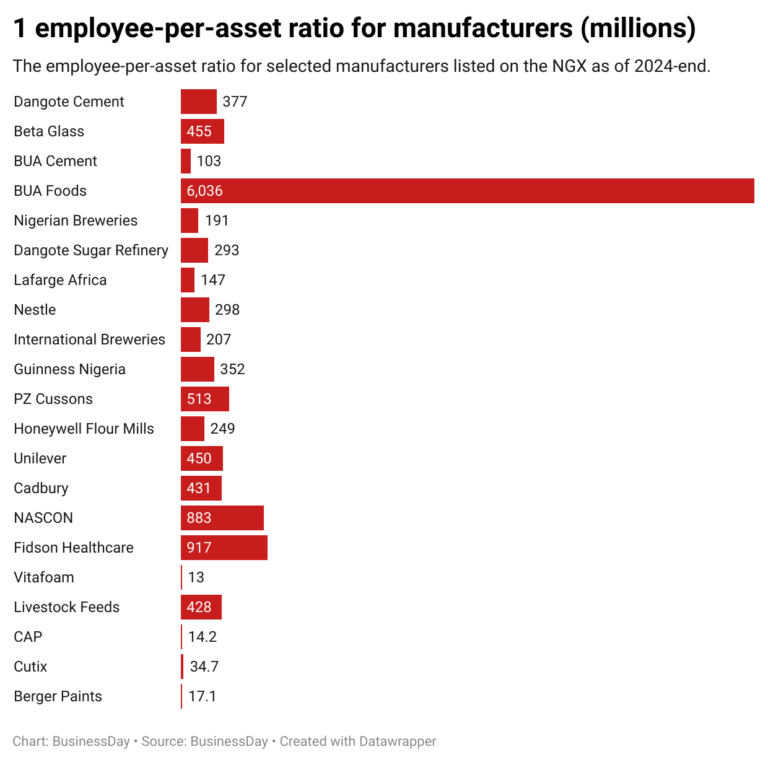

In 2024, Dangote Cement stood out as Nigeria’s largest publicly listed employer, with 21,639 workers on its payroll. Backed by N5.74 trillion in total assets, the cement giant effectively operated with one employee for every N377 million in assets. This ratio captures the labour-heavy nature of Nigerian manufacturing.

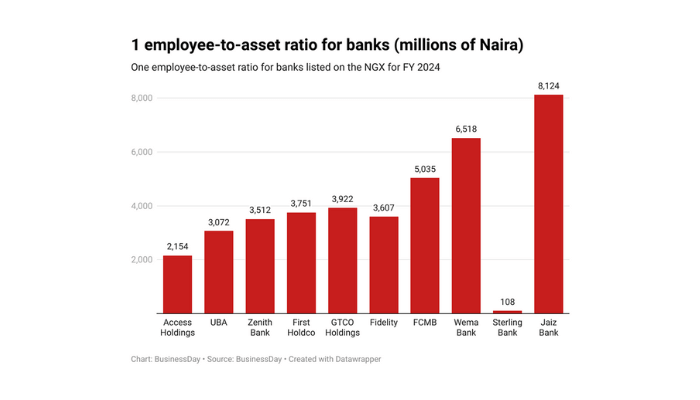

FCMB Group, by comparison, managed N7.54 trillion in assets with just 3,796 employees as of FYE 2024. The mid-tier bank operated at an efficiency level of one employee per N5.03 billion in assets.

Essentially, for FCMB, the figure underscores the banking sector’s dependence on automation and resource optimisation.

The chasm between these ratios offers more than a statistical contrast. It reflects the structural realities of the Nigerian economy, where manufacturing remains deeply labour-intensive, while banking has matured into a sector in which technology and scale sharply reduce the marginal cost of adding customers.

The divergence also carries broader implications for job creation in a country where an estimated 93 percent of the labour force operates informally.

Read also: Why banking system liquidity declined in Q2 2025

Banking vs. Manufacturing: A Tale of Two Economies

Banking and manufacturing collectively shape much of the Nigerian Exchange’s economic footprint, making them two of the clearest mirrors of how corporates absorb labour.

BusinessDay’s analysis shows that the 10 listed banks held N167.7 trillion in assets in 2024, supported by 58,550 full-time employees across local and foreign subsidiaries. This translates to one employee for every N3.56 billion in assets, an indicator of an industry where digitalisation has replaced many traditional roles.

Manufacturers tell a different story. The 21 listed producers controlled just N16.1 trillion in assets, barely 9 percent of the banking sector’s total, yet employed 41,453 full-time workers. That is one employee for every N274 million in assets, revealing how factories, plants and supply chains absorb labour at a scale that financial institutions no longer do.

Inside the Numbers

Zenith Bank led the banking sector with 10,520 full-time staff overseeing N31.2 trillion in assets as of 2024. First Holdco followed with 9,948 employees managing N26.5 trillion.

UBA, with N30.3 trillion in assets as of FYE 2024, had 9,316 full-time employees, reflecting one employee per N3.07 billion in assets. Access Holdings with N41.5 trillion in assets had 8,939 staff, reflecting one employee pe N2.15 billion of assets.

In manufacturing, the contrasts are even sharper. Dangote Cement tops the list with 21,639 workers, followed by Dangote Sugar’s 2,978 employees, supported by an asset base of just N1 trillion. Nestlé Nigeria, with assets of N858.7 billion, employs 2,565 workers, roughly one employee for every N339 million in assets. In terms of employee-to-ratio, BUA Foods was the most divergent, as its N1.24 trillion assets had 750 staff, reflecting one employee per N6.04 billion in assets.

While these headline figures offer a useful cross-sector comparison, they obscure a deeper nuance, the rising role of outsourced and contract staff in banking.

Banks increasingly rely on third-party labour, a practice far less common in manufacturing, but disclosures remain thin. GTCO, for instance, spent N32.4 billion on outsourced staff in 2024, compared with N88.7 billion on its direct employees. While the bank does not publish its outsourced headcount, the scale of expenditure provides a strong signal. Official employee numbers understate the sector’s true labour footprint.

This outsourcing trend blurs the lines in any employee-to-asset comparison and complicates attempts to fully measure how labour-efficient banks are.

Read also: 10 stocks that grew over 1500% on the NGX since 2015

The Employment Question: Why Manufacturing Still Matters

A simple projection illustrates the depth of the employment gap. If Nigerian manufacturers controlled the N167.7 trillion in assets currently held by listed banks, their labour profile suggests they would need at least 450,000 full-time employees. This is almost eight times the size of the banking sector’s disclosed workforce.

The picture becomes even clearer outside the stock market. The unlisted Dangote Refinery and Petrochemical Complex is believed to host a workforce of 57,000, nearly the size of the entire staff strength of listed banks combined. Dangote Industries has signalled plans to add as many as 65,000 more workers as the refinery and adjoining facilities scale up.

These contrasts highlight an often-overlooked structural truth: Nigeria’s manufacturing sector is central to any credible plan for mass employment.

While banking will continue to lead on returns, innovation, and asset growth, it simply cannot absorb labour at the scale Nigeria requires. Millions enter the labour market annually; banks add only a few hundred roles in a typical year.

Manufacturing, by contrast, creates jobs not only within factories but across supply chains, transport, logistics, agro-processing, distribution and retail. With the right policy environment, it remains Nigeria’s most reliable vehicle for large-scale employment.

Manufacturing is more than gross value added

Management consultant Adetunji Adeniyi notes in his study, Manufacturing Output Growth and Employment in Nigeria, that the sector’s role in job creation is theoretically strong. Yet, his findings show no statistically significant relationship between growth in manufacturing output and growth in employment.

He cautions that policy must not rely solely on manufacturing Gross Value Added (GVA) as a predictor of employment. Instead, he recommends a cross-sectoral analytical approach that captures linkages, manufacturing forward and backward connections, to estimate the economy’s true job-absorptive capacity.

This nuance matters: manufacturing creates jobs, but without supportive infrastructure, coherent industrial policy, and competitive energy costs, the relationship between growth and employment becomes muted.

Nigeria’s economic structure creates two very different employment realities. Banking thrives on scale and technology; manufacturing thrives on labour and production depth. For policymakers confronting unemployment and underemployment, the message is clear: Manufacturing drives jobs.

Strengthening manufacturing, through infrastructure, energy reforms, competitive financing, and trade policy, remains essential for Nigeria to unlock mass employment.

Leave a Reply