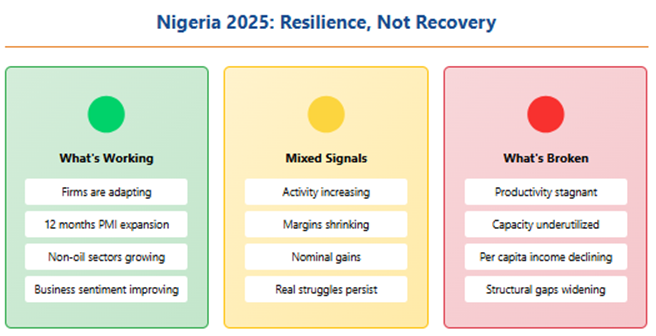

Nigeria’s false dawn? Why rising PMI numbers mask a deeper productivity crisis

The optimism in the headline numbers

Nigeria’s composite Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) rose to 56.4 points in November 2025, marking the twelfth consecutive month of growth, while real GDP grew by 3.98% year-on-year in Q3 2025. Policymakers cite these figures as proof that difficult reforms are yielding results. Yet Nigeria may be experiencing a rebound, not necessarily a recovery. Growth is rising, but productivity is not.

A boardroom view: busy firms, thinner margins

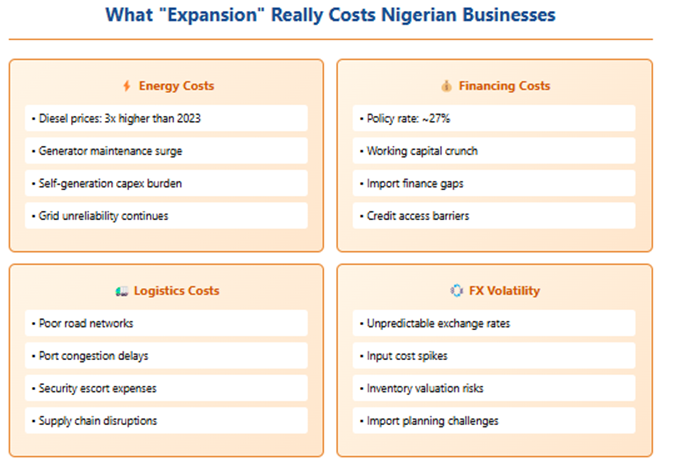

Executives confirm that orders have picked up. Yet firms are wrestling with shrinking margins, elevated input costs, exchange-rate volatility, and energy shortages. Headline inflation has eased to 16.05%, but “slower inflation” at 16% is hardly benign. Companies face much higher diesel prices, expensive imported inputs, and interest costs with the policy rate around 27%. The PMI tells one story; profit-and-loss statements tell another. Activity is up, but profitability is not keeping pace.

Read also: NESG identifies productivity, structural reforms as vital catalysts for economic expansion

A nominal rebound in an economy under pressure

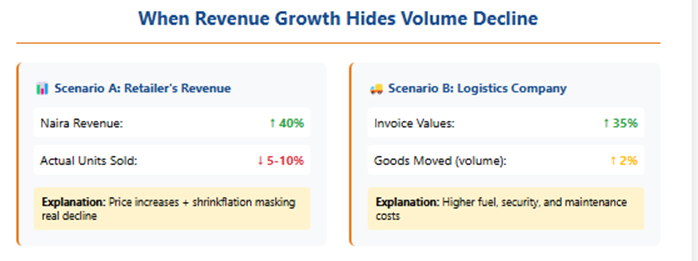

Nigeria is experiencing more of a nominal recovery than a genuine productivity renaissance. The improvement is driven significantly by price effects and inventory restocking. Firms are turning over larger naira values without necessarily expanding real output. In high-inflation environments, nominal indicators often exaggerate underlying strength. Nigeria simultaneously struggles with a structural decline in productive capacity and rising costs in every input market. Power supply remains unreliable, financing is expensive, and logistics are constrained. Firms adapt by raising prices or cutting pack sizes. The PMI records the churn as “expansion”, but activity and progress are not the same.

Manufacturing expansion on paper, strain on the factory floor

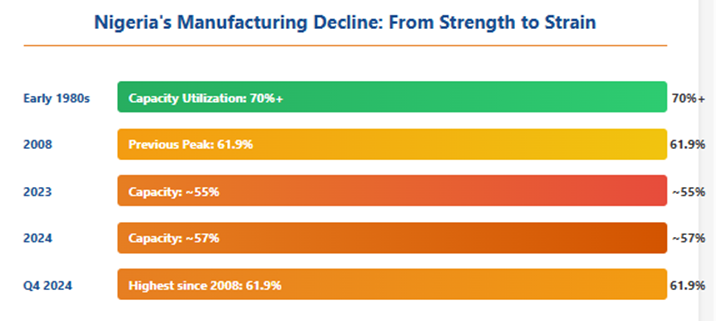

Capacity utilisation in manufacturing improved only marginally, from around 55% in 2023 to about 57% in 2024. Many factories run at 30 to 50% of installed capacity due to foreign-exchange constraints, expensive energy, and weak demand. Real growth in manufacturing was just 1.25% year-on-year in Q3 2025. Yet the manufacturing PMI signals expansion. Firms are spending more to produce roughly the same output—or less.

Services: More activity, not necessarily more value

Services now account for the bulk of Nigeria’s non-oil GDP. Demand for logistics, hospitality, and professional services tends to increase during volatile periods as firms manage disruption. But an expansion in services does not automatically translate into higher productivity. A transport firm may need more trips to move the same volume. Services GDP and PMI rise, yet efficiency and profitability remain under strain.

Read also: Why companies must prioritise workers’ fulfillment to boost productivity in 2026

A productivity recession inside an activity expansion

Nigeria’s PMI is accurate in signalling that firms are busier. It is misleading if that busyness is equated with sustainable prosperity. Nigeria is experiencing a productivity recession inside an activity expansion. Per capita GDP in real terms remains below pre-2014 levels, and output per worker has stagnated. Years of underinvestment and inadequate infrastructure have eroded the economy’s ability to turn effort into value.

“Until Nigeria resolves its deep-rooted productivity problem, the recent PMI surge will remain an encouraging sign of resilience, not yet proof of a new era of sustainable prosperity.”

A consumption-heavy, investment-light pattern of growth

Nigeria’s economy remains heavily consumption-driven. Household consumption expenditure accounted for about 55.8% of GDP in Q4 2023. Households are spending more on basics largely to defend eroding real incomes. This spending shows up statistically as activity but does little to raise productivity. Consumption-led growth under inflationary pressure can entrench vulnerability.

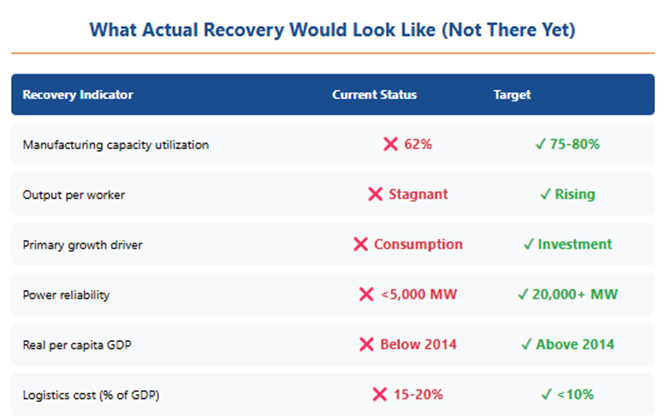

What real recovery would actually look like

A genuine recovery would show sustained increases in output per worker and rising capacity utilisation, climbing towards 70–80%. It would be anchored in investment-driven growth, especially in energy and transport infrastructure. To get there, Nigeria requires structural reforms: power-sector restructuring, export-competitiveness programmes, lower regulatory friction, and a predictable foreign-exchange framework.

Reading the PMI without mistaking it for destiny

The PMI remains a valuable signal of business sentiment and short-term change. It tells us Nigerian firms are adapting, not collapsing. But leaders must resist mistaking momentum for transformation. Activity is not the same as competitiveness. Until Nigeria resolves its deep-rooted productivity problem, the recent PMI surge will remain an encouraging sign of resilience, not yet proof of a new era of sustainable prosperity.

Read also; Nigeria’s Productivity Crisis: Why Hustle Can’t Build a Nation

Dr Oluyemi Adeosun, Chief Economist, BusinessDay.

Leave a Reply